What’s So Great about Executive Function?

Posted: May 13, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: belly breathing, cognitive flexibility, executive function, inhibitory control, resilience, scaffolding, self-regulation, self-talk, working memory Leave a comment

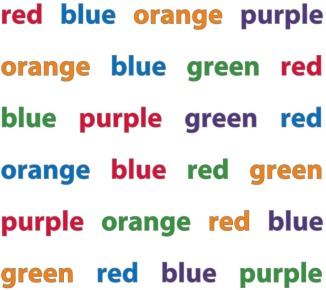

The Stroop test is used to evaluate executive function skills, especially attention and cognitive flexibility. Try it! Say the color, don’t read the word.

Why is everyone talking about executive function?

To begin with, it’s at the heart of self-regulation—that is, our ability to consciously control our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. When it comes to readying children for school and helping them to succeed in both the social and the academic realms, executive function is even more important than IQ.

And according to a study of 1000 children whom researchers followed from birth to age 32, good self-regulation creates healthier, wealthier, and more law-abiding people, whereas poor self-regulation leads to trouble paying attention, following directions, and building and maintaining positive relationships.

So what exactly is executive function?

There are three core executive functions:

- Working memory is the ability to keep information in our minds for a short period while we work with it.

- Cognitive or mental flexibility permits us to shift our focus, adjust to new demands, information, and priorities, fix mistakes, and come up with alternative solutions to problems.

- Inhibitory control is the capacity to control our impulses and think before we act, or in the words of neuroscientist Adele Diamond, “to resist a strong inclination to do one thing and instead do what is most appropriate.”

By working together, these three executive functions lay the foundation for the higher order skills of planning, reasoning, and problem solving.

How do children learn these skills?

Children begin to acquire executive function skills in infancy (think of the baby soothing herself with her thumb or pacifier), and early childhood is an especially fertile period for developing them. We can see this happening before our eyes as toddlers and preschoolers learn to share, wait for a turn, understand rules and directions, calm themselves, and empathize.

But executive functions don’t develop automatically. They depend on the external guidance and support of parents and teachers. By modeling self-regulation ourselves and by providing warm, sensitive, and responsive care, plentiful opportunities to practice self-regulation, scaffolding children’s learning so that they can do what we ask, and reinforcing effort, persistence, and focus, we can help their executive functions to become stronger and stronger. At the same time we are building resilience.

Children who lack these skills need our support the most. Living with toxic stress—for example with neglect, maltreatment, violence, caregiver mental illness, or poverty—disrupts children’s brain development and often robs them of the chance to develop their executive functions. But research shows that children with poor self-regulation actually make the largest gains when they have our support and guidance.

It’s important to improve these skills early because executive function problems grow over time. Diamond says that increasing children’s executive function could even help to close the achievement gap in school and health.

How can teachers enhance executive function?

Several curricula (PATHS, Chicago School Readiness Project, Tools of the Mind, Montessori) show signs of improving children’s executive function, but the research evidence is still weak. However, it is very clear that lots of practice is imperative. Here are some tips to use in your own classroom:

- Work on developing secure relationships with the children you care for. A warm, sensitive, and responsive relationship with a child is the basis for all positive change.

- Create a stimulating and well organized classroom environment with consistent rules. Minimize distractions, remove things that trigger impulsive behavior, and provide reminders and memory aids (such as a picture of an ear to help children listen). With this assistance, children can practice inhibiting their own impulses and following your directions instead.

- Bear in mind that negative emotions such as anger, depression, stress, frustration, and loneliness dispose us to pay less attention, respond impulsively, and even act aggressively. Children having a hard time at home need extra support, monitoring, and guidance; and when they behave inappropriately, a calm, warm response is likely to be more effective than a harsh one.

- Explain the reasons behind your actions and decisions. This enables children to internalize the message.

- Give one direction at a time.

- To help children calm themselves when they’re upset, teach them to recognize the clues their body gives them. Then teach them the turtle position (cross your arms, wrap them around your body, take a deep breath, and then plan how to respond) and/or belly breathing (lie on your back with a small stuffed animal on your belly, and breathe slowly in through the nose and out through the mouth, which rocks the animal). (If you have no stuffed animal, you can put your hands on your tummy.)

- Teach children self-talk. To help them act appropriately, they can quietly tell themselves what to do or count to 10 forwards or backwards, either out loud or in their heads. This helps them to think more rationally.

- Tell stories, and have children tell them, too. Write them down or ask the children to illustrate them, and discuss the feelings in them.

- Schedule lots of time for pretend play, and ask the children to make a plan for what they intend to do. Supervise and ask questions about what they’re doing.

- Use games and songs that require children to pay attention and remember the rules: Simon Says, Red Light/Green Light, memory, walking on a line, follow the leader, freeze dancing, dancing to fast and slow music, singing loud and soft, “Head and Shoulder, Knees and Toes,” “BINGO,” “She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain,” “The Hokey Pokey,” “Five Green and Speckled Frogs,” etc. Puzzles and matching and sorting games (by size, color, shape) also help develop executive function. When children have mastered a game or a song, tweak it to challenge them more, e.g., in Simon Says, change the cue to follow Simon.

- For more ideas, see Enhancing and Practicing Executive Function Skills with Children from Infancy to Adolescence by the Center on the Developing Child of Harvard University; the November 2014 issue of Zero to Three; and this video on executive function by Alberta Family Wellness.

How many of these strategies do you use in your classroom? Have you seen any improvement in the children’s self-control? How hard is it for you to model self-regulation? What do you do to keep your cool when the going gets tough?